Being the analog girl that I am, I happily slurped up Film Soup, an article featuring an interview with artists Tom Evans and Barbara Murray, written back in March of this year. Film Soup introduced the reader to the concept of film soaks and how to create film soups for oneself. I was very excited to find this article, learning new techniques from Tom and Barbara, and finding reassurance to know not only that people are using film, but that they are also experimenting with it, pushing the boundaries and exploring further the art of film photography.

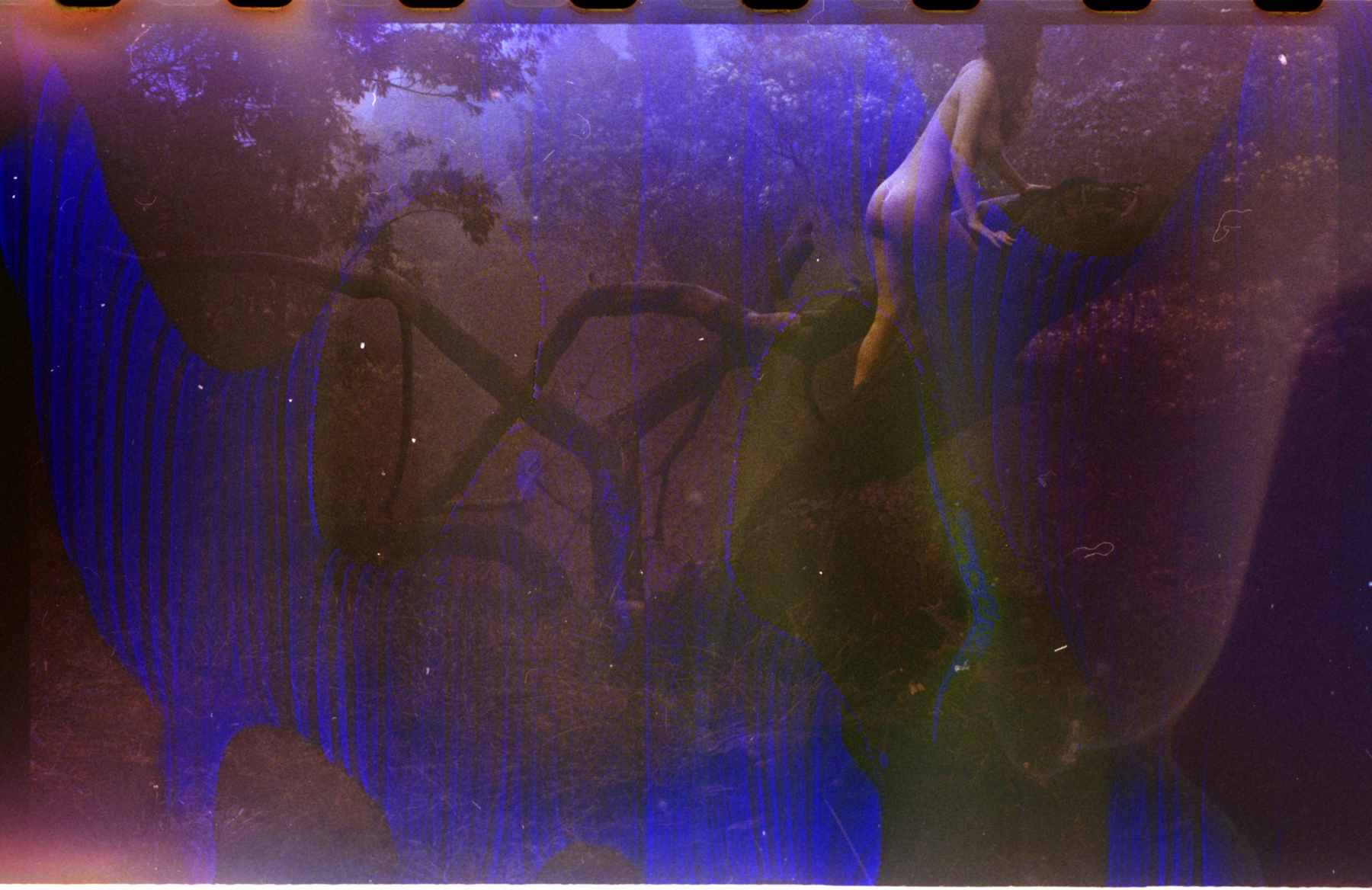

I began experimenting with my film a couple of years ago after discovering the work of photographer Brigette Bloom, who soaks her film in various soups but is most known for using her urine. I tried this technique after falling in love with her work and the unique results given from this taboo ingredient. I found that the colors and patterns created by using urine as the sole ingredient in a film soak were very different in comparison to the results I had achieved from using random household cleaning products and kitchen condiments. Within this experiment, my urine, or as we call it here in Hawaii, shi shi, created many interesting and even cosmic spots that would appear perfectly within the compositions of my images to create portals and tunnels for my subjects. My shi shi soak struck down patterns like railroad tracks along the entire strips of negatives, resulting in perfect geometric shapes and designs, like something you might expect to see underneath the lens of a microscope.

The colors vary depending on the pH of your body, so the results are always very different and I never really know how it all works. After all, I am an artist, not a scientist, although these days I feel slightly like an alchemist. I know that I could be better at recording what I eat and drink before soaking my film in my shi shi, and documenting the length of the soaks and the duration they take to dry before I use the film. However, the mystery of the unknown inside the tiny dark canister where the magical moments are kept is a part of the fun and beauty to me. I like the film being a part of the creation. Why should I think that I am solely in control of the results? I am merely the body that pushes an idea and then a button.

The colors alone are a way to satisfy the need for an effect, something widely desired in online imagery these days, after the popularity of smartphone apps and social media platforms such as Instagram. Yet I find much more satisfaction by knowing that I created these effects myself, with my own body nonetheless.

They are random. None of it can be planned. The film soaks in it's mysterious ways and there is no duplication. The results are always different. The colors are never the same. The patterns are unique to one another. Even if you soak your film in the same ingredient from the same trip to the loo, it will make it's own bed and lie where it pleases atop your film, it's imprinted slumber changing it forever. Some call the results of experimental art happy accidents, but I don't believe in accidents. Every decision affects the outcome. Every drop dictates the direction. Each moment creates the next. I am a true believer in rhyme having a reason, not in coincidences but perfectly mapped out fate, steps to learn to a known dance. It is because of these personal beliefs that I am so content within film and the intricate variables it encompasses.

My techniques are pretty similar to Tom and Barbara. However, I tend to soak my film much longer and always before shooting on it. I like to soak my film for at least a week, sometimes two. Just like soup, the longer you wait, the better it is. It needs to marinate and do a dance with chemistry. I recommend monitoring it by pulling the film out by the tab just a little bit to make sure your soup is not completely eating all the emulsion off. After soaking my film in the soup, which I always do in a jar with an airtight lid, I pour the soup out and let the film drip dry until it is ready to be used. Depending on the environment, the film can take anywhere from a week to two months to fully cure. I see this process as more than just a drying period, since something is still going on inside the dark canister.

After the film is dry enough, I cross my fingers and load it into my camera which loads the film through automatically. If it's not dry enough, it won't load at all and you will know to wait. Patience pays off and this process is not for someone wanting instant results, it takes time and a little encouragement. My old professor used to have conversations with film when I would ask him a mathematical question about pushing or pulling my processing. I thought he was kinda coo-coo but now I understand that film is living and breathing and has a personality of it's own.

Recently, since moving to Maui, I have begun processing my own color film. Unable to find anyone who offered this service on island, I ordered a kit of color chemistry and got to work in my outdoor kitchen, serving perfectly as a well ventilated darkroom. I have now cut out the middleman and the risk of a lab refusing my souped film covered in something interesting like my shi shi. In addition, it is really empowering to be self relient and working at home in the comfort of my outdoor kitchen, where I am in my zone: under the stars, listening to the frogs, and doing a dance with chemistry.

CONNECT

Grace Hazel resides on top of a mountain in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean. She sleeps in a yurt with a red door and lives with her best friends on a vegetable and flower farm, where the night is black, stars scream at you, and the frogs and birds are the daily chorus. You can connect with her on Tumblr, Instagram, and on her website.