People have said since Dwane’s Photo, the last Kodachrome lab in America, stopped processing Kodachrome in 2010 that Kodachrome was dead. The iconic slide film that had dominated magazine covers, movies, newspapers, and your family slides since the 1940’s was obsolete.

People have written songs about this film, crooning the words, “Mama don't take my Kodachrome away” in vain as Kodak announced in 2009 that the last variant of Kodachrome, KR64 in 35mm, was to end production. Once available in nearly every format, and in speeds of ISO25, 40, 64, and 200 it was down to only a single format, a 35mm “pro” ISO64 film.

Everyone said this was the end, that processing Kodachrome was “impossible” and that the bright red canisters so iconic to the world of photography would be relegated to nice display pieces, to sit on shelves and never capture light as they were designed to.

I’ve long loved the look of Kodachrome, its electric reds and bright greens, somehow more real than reality itself even many decades after it was developed. Glimpses of the past perfectly rendered in a tiny transparency. However I had never shot that film. In my wanderings through all the emulsions available to me I missed Kodachrome before it was discontinued.

After discovering this, I began to research the film and discovered it used a process known as “K-14”, much different than modern film’s C-41. K-14 used a toxic color coupler that was no longer in production, which prompted Kodak to end it’s 75 year run. Every person I talked to repeated that it was simply impossible to shoot it in color any more, sure you could develop it as black and white but color was just not ever going to happen.

Now as a self professed armchair photo-chemist, this answer seemed crazy to me. If we’d done it once we could do it again, I vowed to prove it possible!!!

Kodachrome is essentially a sandwich of Black and White films. Unlike C-41 color, where each layer has it’s own color couplers built in Kodachrome relies on those color dyes being added in the development process, making the film simply a sandwich of several color sensitized black and white emulsions. This means that Kodachrome’s development process is far different than the traditional C-41 or E-6 color of today.

I started out reading the manuals for the Kodak K-14 processing machine which outlines the process of development from start to finish giving me a baseline for what my process would need to emulate. This turned out to be a staggering 14 steps to completion.

I then pulled the MSDS filings for the chemistry for K-14, which reveals what the chemistry in the process was using. I attempted to find sources for the chemistry, but as others had already told me some of the couplers were simply no longer available. Not one to admit defeat so readily, I began researching color coupling processes which led me to some very old texts from around 1913 on the beginnings of color coupling process. This finally led me through several steps of trial and error to three complimentary color couplers(Cyan, Magenta, Yellow) that would react to exposed silver in the Kodachrome exactly as I needed them to. We were in business… Or so I thought.

It turns out that chemical supply houses don’t like selling random chemistry to non-certified labs, which made it very hard for me to source the chemistry I needed. Through the help of a very nice person at one of the chemical houses, I managed to source some couplers very close to the original couplers from the documents I’d been researching that they thought should be close enough to pull off my great experiment.

While I waited for those to arrive, I sourced a pair of color filters, one red and one blue, and a white balanced LED flashlight so that once my chemistry arrived I would be ready to go.

On the day of testing I shot a few images on a roll of freezer stored KR64 and went into the dark room to load my tank. My process is still somewhat evolving, but these are my steps.

- Develop the film for 14 minutes at 105F in HC-110B.

- Wash.

- Squeegee the film with a soft sponge to remove the remjet backing.

- Expose through the back of the film with the LED flashlight and red filter.

- Develop for 3:30 at 105F in the Cyan coupler/developer.

- Wash.

- Expose with LED flashlight and blue filter through the front of the film.

- Develop for 3:30 at 105F with Yellow Coupler/developer.

- Wash.

- Expose with LED flashlight and no filters (white light)

- Develop for 3:30 at 105F Magenta coupler/developer.

- Wash.

- Bleach for 6 minutes with Ferricyanide bleach.

- Fix for 8 minutes with standard B&W fixer.

- Wash.

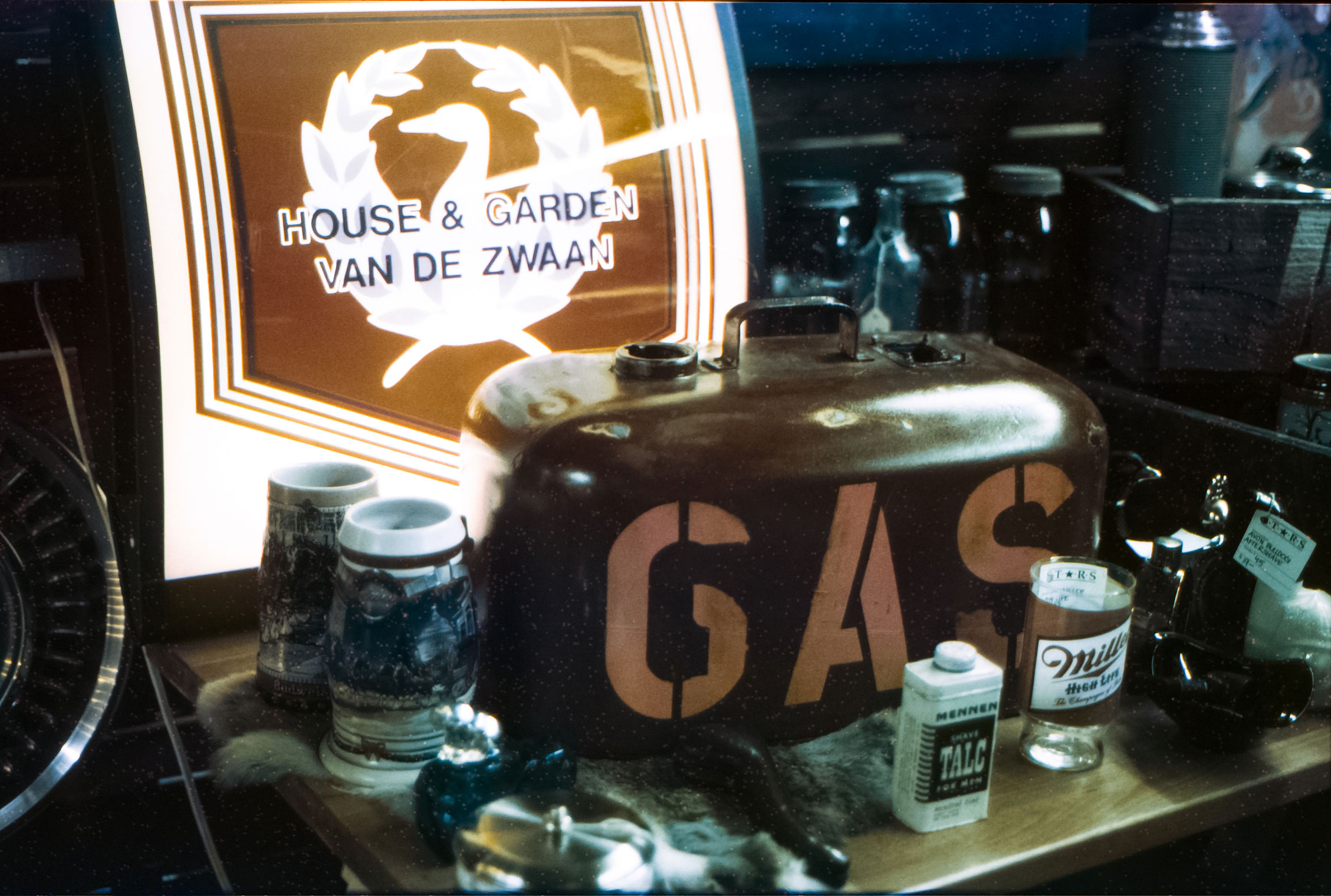

I was ecstatic! After removing the film from the tank, I had slides! In color… But not particularly well color balanced. The process was close, but not perfect.

I quickly realized I had flipped the order of two of my couplers, doing cyan and magenta in reverse which resulted in funny colors. I quickly went outside with another roll to shoot some photos of my classic car and headed back into the lab to repeat the process, resulting in these images:

With colors much more in-line with what they should be I knew I was close to success. I proceeded to research, and read, and adjust my coupler recipes, and repeat again and again with monotonous detail that I won’t bore you with in this article until my results began to mirror the colors I expected.

I’m still tweaking the process somewhat to get as close to the classic colorscape of Kodachrome with every roll, but as it sits now. Kodachrome is not dead, its very much alive in my small laboratory, and I plan on keeping it that way as long as possible!!

Connect

Kelly-Shane Fuller is a creative concept portrait photographer based out of Portland Oregon. He loves shooting portraits with a story especially ones with a cinematic feel. He has found that quite often medium or large format film provides the best look for this style of work and has managed to carve out a niche where he can make film photography work in the high paced world of magazine, commercial, and fashion photography while still producing images at the speed digital demands.

When he's not shooting in studio he's obsessively restoring vintage film cameras(supposedly for resale), restoring classic cars, and hanging out with his wife and son.

You can find more of his work on his profile page in the FSC, his personal page and his Instagram feed.